Reflections on power and belief

Final paper of my study year at Waseda

Preface

The academic year has reached its end. Classes are finished. A hot, humid summer has come overnight and replaced the freshness of spring, filling the air with its innumerable intense perfumes. People that have become part of my life are making their preparations to walk out of it; some only for a while, many others permanently. Suddenly, a feeling of emptiness has come over me. I feel like I am in a vacuum; something has passed away, but it has not yet been replaced by something new. I somewhat fear the return to the country that I more or less consider my home – although the concept of home has become increasingly unclear and undefined, and I am not sure whether or not I will feel at home when I am back. As I am sitting in my small, messy dormitory room, I think about this past year. Lately, I have spent so much time studying some very interesting things that I hardly had any time to reflect upon the things I was studying. Right now, I am. I am thinking about the significance of what I have been studying this year, as well as the personal experiences I had while I was here.

Reflecting upon my Japanese year, it becomes clear that there have been a few central themes. These themes are connected to topics I have been thinking, talking, reading and writing about, to the things I was studying, and to my experience of being a part of Japanese society. On two of these themes, the use of ideology and the concept of history, I wrote two papers during the first semester. Some other, closely related themes have been reoccurring in writings and discussions. In this paper, I will examine some of these themes once again, thereby sometimes referring to things I studied, to personal experiences or to writings and ideas from others.

The three themes I shall discuss in this paper are truth, fear and mythology. All are closely connected to each other. They are closely connected to topics such as religion, belief, ideology and power, too. The purpose of this paper is neither completeness, nor consistency; it is a playful philosophical approach to wind up the intellectual process I have gone through this year, examining questions rather than answering them, while inevitably raising new questions and themes. I will use different literary forms and approaches for exploring these topics, as this may help me to look at things from different perspectives. The result is a short, experimental patchwork of short essays, stories and quotes.

I. Truth

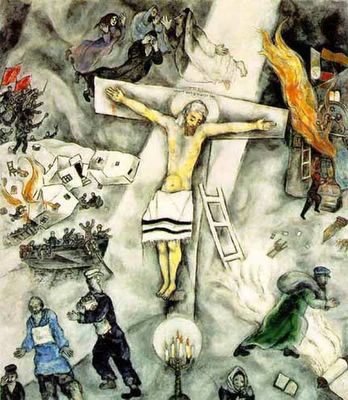

‘I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.’ (Jesus Christ, as quoted by the evangelist John, John 14:6.)

‘What then is truth? A movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and; anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished, and which, after long usage, seem to a people to be fixed, canonical, and binding.’ (Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘On truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense’)

‘The only thing we can be sure of is of the fact that different, contradicting interpretations exist – whether or not they are true does not concern us; the only things that concern us are the social and psychological implications of these interpretations. Ideologies [i.e., truths] provide people with certainty about an existence that does not provide any certainty, and thereby replace that very existence.’ (Aike Rots, ‘Ideology – A First Exploration’)

AR: Did you really say that?

JC[1]: The answer on that question depends on your definition of reality.

AR: I mean: is it a historical fact that you spoke those words?

JC: No. I didn’t speak English at the time.

AR: The equivalence in your language. Is it true that you spoke these words?

JC: This is one of my most important, best-known quotes. It summarizes effectively why people should be Christian. It is brief, powerful, and dramatic. It is one of John’s best literary accomplishments. The significance of the truth of this quote for more than a billion people in this world is enormous, as it provides them with a necessary framework for living their life. Of course it is true.

AR: I understand why this quote is significant. But I am not interested in such a politically correct answer. Things are not true, simply because it is useful that they are true. The problem of such a utilitarian circular argument is that it is only concerned with the need and the purpose of things, but it doesn’t tell us anything about the intrinsic quality or validity of things. What I want to know is: is it historically true that you said this?

JC: So what if I did? Who cares? Would it change anything if I indeed did say this? Or if I didn’t? If I did, I said it in a particular context, for a particular reason, with a particular meaning in mind. But my own intention at the time is completely irrelevant. People impose their own interpretations and meanings on me, claiming them to be absolute truths that exceed place and time, ignoring my being part of and reacting to a society that was facing social crises. So would it change anything if I would declare that I did not say this? Do you think people would believe me? Of course not – the truth of their explanation would be challenged too much. And as this truth provides them with meaning at a fundamental level, taking away this truth would challenge their very lives.

Most people are not going to allow this to happen, I assure you. And they have a very powerful argument: it is written. It is written that I said this, and therefore absolute and unchanging – even though I never met the person who wrote this and don’t know why he chose to write this. The problem of a written revelation, a written word of God, is that it becomes impossible to change anything – as if God Himself is static, unchanging and reactionary! Even if the Holy Texts of the World indeed are written, revealed or inspired by God, he had to adjust to the frame of reference of his audiences, by using their imperfect languages and symbols and expressions they were able to understand. That would mean that even divine truth is not absolute, as it is always in the process of changing and reacts to a certain social, historical and linguistic context. But people need their divine truths to be absolute, because it provides them with comfort, gives them direction, and prevents them from questioning the status quo of their current life.

FN[2]: But isn’t that the point of living? That we question the historically and socially constructed myths and lies that are used to prevent us from thinking ourselves? That we recognize how certain opinions, lies and other fictions lose their symbolic relevance when they come to be seen as truths? Why are they perceived as the truth by the masses? Because those who have power use these truths to legitimize their own power. Why do you think people try to convince others of the truth of their opinions? Because if your position is defined as corresponding to the truth, you have the perfect justification for your actions. You have power. The more people think your claims are true, the more you will be able to legitimize certain behaviour or policy as it is perceived as serving the truth. That’s power. The challenge is too recognize these power structures and dismantle the so-called ‘truths’ as being constructions.

AR: But what about scientific truths? E=MC² is always true, isn’t it? That doesn’t serve a particular power structure. Or does it?

FN: It is a symbolic representation. In this case, it is a symbol that serves very well to explain certain natural processes. However, it is still a symbol. The ultimate purpose of any symbolic representation is to provide meaning – a meaning that is shared by different people. Scientific ‘truths’ are symbols; explanations, labels. But they claim to be truths that exceed time and place. They are used to legitimize power structures in the same way as religious truths. The primary function of universities – the institutions in which these truths are created, discussed and reshaped – is to complete the socializing process of young people in a certain society with a certain ideology, and provide societies in which the reason is worshipped with a rational justification for the system – the justification that in the past was provided by religion. What’s the difference between ‘the king should rule the country, because he is a representative of God, which means that he knows best what is good for his people’ and ‘this country should be governed by an elected government, because logic demands that if people choose their own government, their interests are preserved in the best way’. As people need answers and explanations that are easily digestible, as people want others to tell them what they should think, naïve positivism flourishes. Like our friend Jesus here just said: it is written, so it is true. Scientific data are treated in exactly the same way as holy texts – only a few people really study and criticize them, whereas the majority of the people accepts them as true. Statistical data are perceived as true by the masses – thus, they are used to legitimize policies.

JC: The problem is not so much that people believe certain things, though. Belief can serve to establish social change and improvements, to make people act responsibly as a member of a society, et cetera. My personal belief has urged me to be active, to mobilize people – the results being not exactly what I had expected them to be, but that’s a different issue. My point is, the problem is not belief as such. The problem is that belief has come to be something absolute. Religious belief is no longer a matter of shared symbols, as is primary function always was. Religious belief has been irrevocably transformed because people have started defending it by applying rational, logical criteria, which means that it is either true or untrue, right or not right, correct or false. There is nothing in between. The symbolic significance of mythologies, images and rituals has come to be neglected. In stead, we have to choose whether we believe these symbols to be ‘true’. Why did you ask me if I really said this sentence? Because you want to know whether or not it is true. Why do people who feel attracted to the symbolism of Christianity have to accept the divinity and the resurrection of its founder, me, as historical facts? Because truth has come to mean rational, historical truth. Symbols are not recognized as symbols anymore. As a result, beliefs have to be logically consistent. One cannot believe in A and B at the same time, because A and B have another, contradictory explanation of the human condition. Truth has thus come to be exclusive. If you share my truth, we share an identity. If we share an identity, we share interests. Those who don’t believe the same thing, either have to be converted or combated.

FN: Both converting people or fighting them serves to enlarge ones own power. So ‘truth’ is used as a means to legitimize a certain power structure – either consciously or unconsciously.

AR: But does that mean there is no truth whatsoever? What about ethics? The categorical imperative? Isn’t the imperative not to harm or hurt others a truth? If you say there is no truth, that means no system of ethics can exist that is based on anything else than practical use. But doesn’t that lead to nihilism? If there is nothing more we can base our behaviour on, if there is nothing we can be sure of, what’s the point of doing things? Wouldn’t that lead to hedonism?

JC: I am not saying truth does not exist. Personally, I have a very strong belief, especially when it comes to ethical issues. Responsible behaviour towards others, striving for social justice, respect for those who have a different background, different habits and ideas than oneself; I consider these very important things. Why? Not because it is written down that we should behave like this – law is not absolute, as it has been created in a certain social and political context, mind you! Not because there is an absolute commandment telling us we ought to do this. But because we want to do so ourselves; because the interactions we have with other human beings that make an appeal to us provoke a sense of compassion. When I feel this, it is true. There is nothing wrong with perceiving things as true! I am not saying there is no intrinsic truth either – although the question remains whether or not this truth can be known by us, and whether or not it is relevant. It becomes problematic, though, when certain symbolic truths come to be seen as absolute, literal truths, as this is usually when they transform into ideologies that serve to establish and protect certain power structures, and deny others the right to have their own symbolic interpretation of life. We should therefore always be willing to question and challenge what we regard as the truth, and ask ourselves what political structure and ideology this truth might serve.

II. Fear

‘Did you hear the story of Mrs. A and Mrs. B.?’

‘What happened?’

‘You know they went to Kyoto

‘Yes.’

‘There’s this temple. They say drinking the water cures you.’

‘I heard about that.’

‘They drank it. Now, both of them are very ill.’

‘They should have known…’

‘You know, I once went to this temple town.’

‘You did? You know you shouldn’t!’

‘Only once, because I’m interested in architecture, you know. But I got very sick the next week…’

‘Our late Prime Minister went to Ise.[3] He prayed there. But he was Christian, you know.’

‘What happened to him?’

‘He died shortly thereafter.’

‘Because of that?’

‘I don’t know…’

(Conversation at a Christian church in Japan

Recently, the draft constitution of the European Union was rejected by a vast majority of the French and Dutch populations, despite the fact that the constitution proposed improvements in the process of democratic decision making, a stronger legal protection for human rights, organizational reforms that would make the EU operate more smoothly and by doing so strengthen its international position, et cetera. When asked why they had voted against the constitution, many Dutch people replied that the developments ‘were going too fast’. The institution EU is perceived as a giant, undemocratic, bureaucratic organization that only costs money and does not meet with the national interests. A leftist opposition party that was campaigning against the constitution made a poster, on which we see a map of Europe without The Netherlands, which have disappeared:

Of course, this is not meant to be taken very seriously. But the use of humour reflects a sentiment that is very real, and therefore should be taken seriously after all. The project of the European integration is perceived as a threat to the own interests and the own identity. In a society that has transformed rapidly and drastically over the last few years, the need for a clearly described national identity has suddenly become very urgent. With the growing necessity of the reinvention of a national identity, the need to point out ‘others’ that are antithetical to this identity has also emerged. Ethnic and religious minorities are an easy target, and it is indeed frightening to see how in a country that used to be famous for its tolerance – even though that tolerance fundamentally was just a pragmatic approach that served national economics, as some historians have argued – in a few years Muslim immigrants have come to be blamed for supposed problems in society, Islamic institutions have been set on fire, and migration policy has become very strict and isolationist. The EU has now come to serve the same role as the immigrants: it is perceived as an extern threat, that has the potential to do serious damage to society and challenge the identity of its members.

Why do I use this example? For several reasons. First, because it shows how political groups utilize and even strengthen the fear of people when it serves their own interest. By causing and stimulating fear, a political group can legitimize its stances and policies. This is not just the case with leftist or ultranationalist parties and politicians. Mainstream governments use the same strategy successfully. A system of colours that warn for a potential terrorist attack is a powerful way to manipulate the feelings of the population – and to legitimize certain government interventions and violations of privacy, for example.

Second, I am puzzled by how a society can transform so overnight. Fear does not necessarily respond to a certain situation; it can also create that situation. Fear for minorities often leads to stigmatization and the intensification of prejudices, which often leads to radicalization among some members of those minority groups, who –understandably– feel threatened in their own identity and feel the urge to protect that. Anxiety thus brings forth self-fulfilling prophecies. But how does anxiety succeed in spreading? How can something vague, a ‘feeling’, spread among and influence large groups in society? There is undoubtedly an element of dissatisfaction involved; when people are not satisfied with their present situation (including their economical position) they are more uncertain about the future; and, therefore, more willing to follow a leader that promises certainty. In the past, we have seen how mass feelings of unease and fear have given rise to mass popularity for leaders who established totalitarian regimes – Germany in the 1930’s is probably the best-known example of a young democracy that became totalitarian. Another possible reason for the spread of anxiety, closely related to the issue of dissatisfaction, can be rapid changes in society. Rapid social changes pose a challenge to established frames of reference – or ideologies – and therefore represent a potential threat. People feel alienated, as has been the case with several Middle Eastern countries; the rapid modernizing process these countries went through in the 19th and early 20th centuries only benefited a small westernized elite, whereas the large urban lower and middle classes were confronted with high unemployment, growing disparities, oppression of religious behaviour and unwanted western cultural influences – this alienation can lead to anxiety, give rise to ideologically based protest movements and eventually even result in overthrowing the regime, as happened in Iran.

As the conversation I quoted makes clear, once a system is established (either a small community or a political regime), fear may be used to protect that system. By clearly defining rules and making people afraid of the consequences of breaking those rules, the system defines its borders and tries to keep people faithful to its ideology, as other ideologies are presented as threats and enemies. This has not just been the case in totalitarian regimes. Portraying a rival ideology as a great danger to peace and wealth, antithetical to ones own ideology, is a strategy that has been used during the Cold War by capitalist countries with regard to communism, for example. As a result, the Other is not just a means for defining ones own identity; he becomes a threat, something people are afraid of – a political tool used by the hegemonic ideology to preserve its own position.

Søren Kierkegaard discussed the topic of anxiety (Angst) in great detail. To him, anxiety fundamentally is an individual feeling; a reaction on the great, existential freedom that defines our being. I do not say this existential anxiety does not exist or influence people; however, I would argue that in reality, fear oftentimes is not an individual, but a social phenomenon, as well as a political tool. People influence and manipulate each other. As is the case in contemporary Dutch society, fear (for Islam, for immigrants, for the EU) basically is a powerful social construction.

III. Mythology

We tend to assume that the people of the past were (more or less) like us, but in fact their spiritual lives were rather different. In particular, they evolved two ways of thinking, speaking, and acquiring knowledge, which scholars have called mythos and logos. Both were essential; they were regarded as complementary ways of arriving at truth, and each had its special area of competence. Myth was regarded as primary; it was concerned with what was thought to be timeless and constant in our existence. Myth looked back to the origins of life, to the foundations of culture, and to the deepest levels of the human mind. Myth was not concerned with practical matters, but with meaning.

(Karen Armstrong, ‘The Battle for God: A History of Fundamentalism’, p. xv.)

What the world supplies to myth is an historical reality, defined, even if this goes back quite a while, by the way in which men have produced or used it; and what myth gives in return is a natural image of this reality. And just as bourgeois ideology is defined by the abandonment of the name 'bourgeois', myth is constituted by the loss of the historical quality of things: in it, things lose the memory that they once were made. The world enters language as a dialectical relation between activities, between human actions; it comes out of myth as a harmonious display of essences. A conjuring trick has taken place; it has turned reality inside out, it has emptied it of history and has filled it with nature, it has removed from things their human meaning so as to make them signify a human insignificance.

(Roland Barthes, ‘Mythologies’)

On hatred, salvation, justice and natural disasters – a first attempt to write a myth

There was a time we all loved each other. All human beings loved each other unconditionally. We used to dance together in the garden that was created by our common ancestors; we used to dance in the place that they had promised us. There was no pain, no suffering, no disagreement. Every once in a while, someone would leave us for the realm of the ancestors, but despite mourning the loss of her or his physical appearance we would celebrate her or his becoming one of the ancestors. When it rained, we took shelter in the houses our ancestors had taught us to build; when it was cold, we wore the protection nature had given us. We thanked the sun and the rain, who so generously nurtured us, for their blessings. We shared our food with them and told them our stories. Everything was perfect. We were together, we were protected by the sun and the rain.

That’s when they arrived. They were jealous. They didn’t receive the blessings – not because the sun and the rain didn’t give them to them, but because they didn’t recognize them. They were hungry, so we felt sorry for them. We shared our meals with them. However, they ate everything. They didn’t leave anything for us, but because they were so hungry, we allowed them to do so. The next day, they did the same thing. They ate all our food. They even demanded us to give them more, which we couldn’t because that would have made us run out of food later that year. That’s when they started threatening our children. They said that if we didn’t give them more food, they would kill our children. They had weapons. We asked the sun and the rain to protect us. But they started eating our children. The sun and the rain couldn’t face the things that were happening. They turned away from us; the sun lost his light, the rain stopped raining. We were desperate. Everything was dark and dry. There was no food left, and they had eaten many of us, telling us it was the only way they could find what they were looking for.

That’s when he came. He told us not to fear, for our suffering was only temporary. He told us to write down his words, for they would save us. He told us to continue loving each other, even though they were eating our children. He even told us that we could become like them when we would be hungry. We loved him, he loved them, but they hated him. He asked them to stop eating the children, but they laughed at him. They told him they were hungry; they told him they would eat him, too, if he didn’t stop preaching. But he told them: if you don’t stop eating those children, the sun and the rain might never return. They asked him how he knew, but he didn’t respond, which made them furious. They couldn’t understand why they needed the sun and the rain. They were approaching something much more real, they said. He asked what it was they were approaching, and they told him it was the truth. He asked them why they would need the truth, if the grass was growing. They spit on him, saying that there could be no grass without understanding the grass. He asked them why they needed to eat other people while searching for the truth. They told him they were so busy finding the truth that they had forgotten where to find food. They told him they had to sacrifice others in their search for the truth. He asked them whether they had found what they were looking for. They told him to be quiet, for they would eat him, too.

Suddenly, the sun and the rain started moving. Everything was turned upside down. The truth was changed completely; what had been light before, was now dark, and what had been dry before, was now water. We took shelter in the houses our ancestors had taught us to build, but they didn’t have anything to go to. We invited them to take shelter in our houses, too, but they didn’t trust us. He tried to save them from the changing world by calling their names and begging the sun and the rain to stop changing everything; but the sun and the rain couldn’t possibly stop the process they had created themselves. They were all eaten by the sun and the rain. And so was he, as he couldn’t let them go, because he loved them too much.

The sun and the rain had returned, and we lived our lives like nothing had ever happened. Without him, though. But we promised him we would never forget him. We had written down his words, which we continued telling each other. Nor would we forget them, as they had been the ones that showed us the danger of running after the truth without appreciating the benefits of the present.

Final remarks

This paper is not really a paper. Rather, it is a reflection of some of the topics I have been studying and thinking about recently. It does not contain any solution or consistently presented argument. However, I hope it does contain some interesting, perhaps challenging thoughts.

The concept of truth is mythologized. The fact that we believe in truth as an independent, undeniable entity shows that it has become depoliticized. Repoliticizing truths – thereby denying their absoluteness – might be one of the biggest challenges that face us. How do certain claims about reality reflect ideological and political interests? What is the historical and social background of something that is perceived as true? How does truth manage to become perceived as such?

This paper might be read as a sequel to the two papers I wrote during the first semester. It might be read independently, too. Basically, writing this has been an interesting thinking practice and a great opportunity for me personally to reflect upon some of this year’s topics once more. It has also strengthened my wish to study more about the diffuse but powerful relationship between beliefs, religion, ideology and politics. I have found that truth, fear and mythology can be used as political tools – exactly because they meet with some fundamental existential questions.

My study year has reached its end. At the same time, though, this year has been a beginning – the beginning of further research on this topic and case studies related to this topic. Hopefully, I will be able to continue the study of the practical and political use of religious ideology in later years.

[1] I am doing the same thing as the evangelists, film directors, writers and many others: I am creating an image of Jesus that does not necessarily correspond to the historical person Jesus of Nazareth. However, there is a difference: in contrast to most of the others, I do not claim this image of Jesus to be ‘true’, as it is my image; I am deliberately using the figure of Jesus with its symbolic significance to articulate some of my personal thoughts and questions. Therefore, this character is fictional.

[2] This is not the historical Nietzsche; it is just another fictional character that might be modelled after what I know about the ideas of Nietzsche, but basically serves to articulate some other personal thoughts and opinions. In fact, the historical Nietzsche was much more optimistic and naïve about the achievements of science than FN is. In general, though, they do share a sceptical attitude towards established truths, which is why I invited Mr. FN for this short discussion.

[3] The most important Shinto center in Japan